Blood clots and the COVID-19 Vaccine

The vaccine and blood clots – risks and benefits

The incidence of blood clots following a dose of the Astra-Zeneca (AZ) vaccine has changed, with the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) stating the preferred vaccine in people under 60 years of age is the Pfizer (Comirnaty) vaccine.

This post is not to tell you whether to get your AZ vaccine or not, but to give some guidance on the risk as we understand it so far.

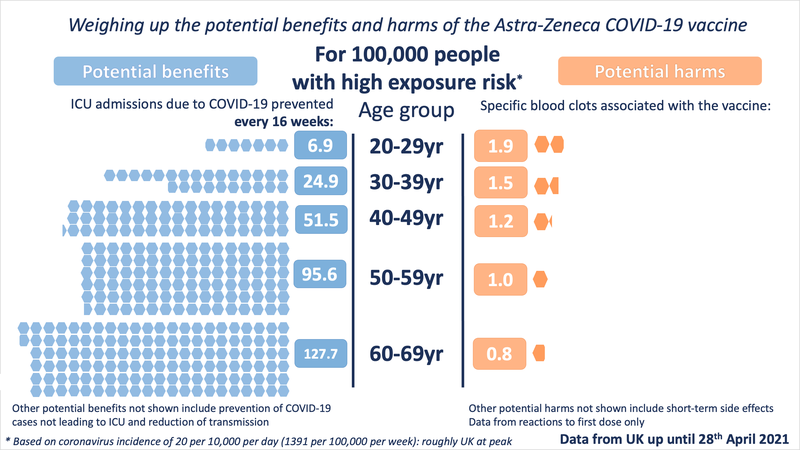

Firstly, not all clots are the same. The clots potentially caused by the vaccine are thought to have a similar mechanism to a condition called Heparin Induced Thrombocytopaenia (HIT), and this new syndrome is being called many things, such as Vaccine Induced Prothrombotic Immune Thrombocytopaenia (VIPIT) and Thrombosis with Thrombocytopaenia (TTS) which I will refer to it as in this post. It appears to affect younger people slightly more disproportionately, though the 50-59 age group also has a slight increase in the incidence compared to older groups.

As of the 4th of April 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recorded 34 million doses of the AZ vaccine given in Europe including the UK. There have been 169 cases of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis (CVST) and 53 cases of Splanchnic Vein Thrombosis. This means 222 cases in 34 million doses, and assuming all of these are due to the vaccine (which we can’t definitely say) this puts the risk at 6.52 TTS cases per million doses given.

Since then updated data from the UK (as of 16th June 2021) shows that the incidence in patients aged 18-49 is 19.6 per million first doses given, and 1.6 per million-second doses.

The mortality rate in these patients in Europe was about 20% when this condition first came to light, but in Australia, it is less than 3%.

How does this compare with clots from other common medicines or lifestyle factors?

One of the most common risk assessments GPs make in regards to clots is the risk associated with the Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill, or ‘the pill’. It’s not a great comparison, because the pill is something people take daily, it’s been around for a long time, and the mechanism by which it causes clots is different to VIPIT and is well understood.

The baseline risk for developing a clot in women not taking the pill is about 4 per 10,000 women per year (0.04%). For women who take the pill, it’s 7-10 clots per 10,000 women per year (0.07-0.1%) or about 1 in 1000.

For pregnant and postpartum women (the time after birth) the risk is 20-30 per 10,000 women per year (0.2-0.3%), but this rate is higher in the 12 weeks postpartum at 45-60 per 10,000 women per year (0.4-0.65%), and highest in the 2 days before and 1 day after giving birth at 300-400 per 10,000 women per year (3-4%).

To compare again, the risk at present of clots from the vaccine appears to be 0.00000652%. But I don’t think it’s fair to compare things like this. Because to understand the risk of something, you must compare it to the benefit provided by that intervention and make a decision based on that.

https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2016/januaryfebruary/risk-of-venous-thromboembolism-in-women-taking-the-combined-oral-contraceptive-a-systematic-review-and-meta-analysis/

Risk vs benefit

In the UK, COVID-19 was and still is running rampant. Lots of people were being infected, many were dying, and many more were left considerably unwell. With current circulating levels of COVID in the UK, delaying the vaccine to 10 million people by 1 week would result in 16,000 more infections than could have been prevented.

If all these people were over 60, then we’d expect 1000 hospitalisations and 300 deaths.

If everyone was 40, we’d have about 16 deaths.

Other than death, hospitalisation and respiratory failure, people with COVID-19 also develop clots at a rate of about 16%. Those who are younger without medical comorbidities are more likely to suffer from ‘Long Covid’ also.

So in the UK, their advice is for people under 30 to have a choice in which vaccine they receive. Because taking into account the number of cases, the number of lives and illness saved by vaccinating, the risk-benefit appears to break even at about age 30.

So why was it 60 in Australia? Because we didn’t really have any community COVID to speak of. The chance of being unwell from COVID if you were to catch it remains the same, but the chance of contracting it in the first place was much lower. But that’s all changed now.

Short-term risk vs long term risk

Again I don’t think it’s fair for people to decide if they will or won’t get the shot without weighing up all the risks and benefits in the long term. While case numbers are still low in Australia, we’re on the precipice of it getting out of control. It had only been so because of extremely strict border control measures, lockdowns and aggressive testing that we could live relatively carefree. Since this won’t remain the case forever, we can’t really think about it as being clot vs no clot.

I think the mindset now isn’t how long can we stay at zero Covid, it’s what we need to be ready for when we (I, you, anyone) catch Covid.

So this is something you might consider when deciding if you go ahead or not.

The Pfizer Vaccine

While it is all well and good that ATAGI has recommended that the Pfizer vaccine is recommended for those under 60, supply remains an issue for the next few months.

While people in phases 1a, 1b and 2a will be eligible for Pfizer, it does leave a lot of people 40 and under without any other indications for vaccine in a precarious position.

Is this all a moot point?

This risk analysis appears to boil down to one simple thing (that is infinitely difficult to measure with certainty) – are you more likely to die if you receive the vaccine or not. Almost anyone who qualifies for 1b because of pre-existing medical conditions, COVID-19 will cause you much more trouble than the vaccine. With the delta variant, this may apply more broadly.

If you are otherwise perfectly healthy and are at risk of COVID (we all are now), then you need to consider all the info above, and consider new info as it comes to light and decide do you want to be immunised now, or wait until another vaccine is on offer.

A final word on assessing risk

Deciding how a risk applies to ourselves or others is incredibly difficult. We’re not good at looking at things over the long term as individuals. If we were, we wouldn’t need to have compulsory super, no one would smoke, skin cancer would disappear and life would be very simple.

Risk is multifactorial, some risk factors compound and others are minimised with multiple variables all at play. In essence, though it is an extremely personal decision.

I hope that the government, our healthy bodies, and the media all do their due diligence in conveying information in an easy-to-understand and transparent fashion.

I (Dr Daniel Chanisheff) had the Astra-Zeneca vaccine before the ATAGI guideline was released. As such, I had my second dose 12 weeks after my first. Being a healthcare worker, I am in phase 1b, and having met patients who have had COVID themselves, and patients who have family members they have lost overseas, I am acutely aware that this is not an Australa-only issue. If I was due to receive the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine today, I would still go ahead and probably do it. I understand there are bigger risks in my life than clots from this vaccine, I see what can happen if COVID infects us, and I want to be able to travel the world again one day. But I won’t tell any patient how to make their decision regarding the vaccine. I hope I can inform you to the best of my ability, and hope this makes your choice easier, even if only slightly.